|

| September / October 2005, Vol. 10, No. 9/10 |

|

Not Just Flying Toasters Aaron Yassin talks to artist Tom Moody |

|

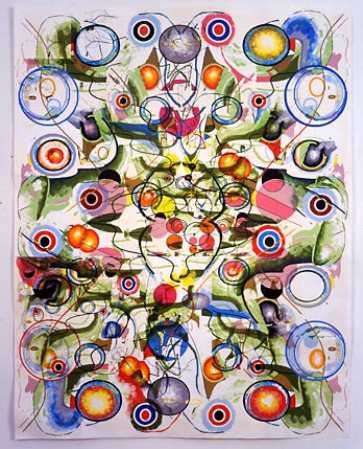

Tom Moody, Swarm , 2003. Ink on paper, linen tape, 53 1/2 x 41 1/2 in. Photo by Bill Orcutt. |

|

Tom Moody began his career painting (with brushes on canvas) and has worked with techniques from photo-realistic to something that would fall under the heading of "bad painting." He still paints, but for most of the past decade, he has done it with digital tools to create an ever-expanding body of work that also includes collages, animations, music, and web-based works.

Moody isn't focused on hi-tech computer art, robotics or software art—he uses simple and even out of date programs like MSPaintbrush. He's interested in the basic tools of our digital age and with exploring their potential for image making.

In addition to his dynamic artistic output, which has been exhibited in solo shows in New York and exhibitions such as "Ink Jet" at the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Moody has maintained a weblog since 2001 at www.digitalmediatree.com/tommoody . Like his artwork, the site is also straightforward in its approach and similarly diverse and comprehensive in its effect. It's an original interactive collection of thoughts, insights, images and musings distributed in real time. Moody took some time to talk to NY Arts about the net, freestanding works, and “truth to materials.” Aaron Yassin: I'd like to talk first about one of your recent works, Swarm . It's simultaneously very mathematically structured and playfully animistic—a remarkable combination. How did you make it? Tom Moody: Before we start, thanks for mentioning the "bad painting" influence! The element of doubt is crucial for me. For Swarm there's a sort of "core drawing," a free-form improvisation of spheres, curving lines, and so forth. I drew it with MSPaintbrush, which is a program that shipped with Windows in the early 1990s. It's clunky but much richer than the current MSPaint. Swarm is printed out at different sizes—100 percent, 200 percent, 400 percent—and each time it's layered over the sizes that preceded it, so you end up with a crude vortex.

AY: Physically layered, or layered in the computer? TM: Well, both. The same sheets of paper are being run through the printer multiple times, and I'm also redrawing the image slightly before each pass, building up a kind of palimpsest of deliberate asymmetries. The layering style is somewhat Picabia-esque. When the individual sheets aren't in the printer, they're up on the wall, just like a painting, and I'm sitting at the computer looking at them and thinking about what adjustments are needed. It's kind of game theory-ish, but I'm also trying to make something quirkily expressive and un-computerlike. At the end, I have a grid of about 35 letter sized overprinted sheets, which are then trimmed and taped together into a large composite.

AY: You use the technology to setup ironic distancing on many levels. For example, it's a painting that's not painted; it's hand made yet it's printed by a machine; it's a "digital" and seemingly reproducible work of art yet it is in fact a unique object. Can you talk about how these relationships contribute to the subject in your work? TM: The cartoony hand is “me” but the work plays with various influences: Abstract Expressionism, Japanese animation, early computer graphics. The self-consciously baroque style makes fun of the meandering purposelessness of nth-generation abstraction, or perhaps I'm trying to create the worst nightmare of people who never liked abstraction, because they see it as too aestheticized or bourgeois. I think there's a relationship in the work between classic modernist painting, made in an era when people were talking about exciting new discoveries such as radio and X-rays, and the early years of home computing, when a new wave of utopian talk filled the air. I like the idea of going back to both Cubism and MacPaint but then making something that's more "wised up" and current.

AY: So, you're looking backwards and forwards simultaneously and using these primitive computer programs to do it. Why? Your fascination in lo-fi technology based art is something you also regularly feature on your blog. What interests you in this work? TM: I started using MSPaintbrush on a temp job that had a lot of downtime. The computer didn't have Photoshop, Paintbrush was standard issue--it looks a bit like the old MacPaint. I liked it as a medium because I thought it demystified the computer. I figured almost everyone had fooled around with one of these early programs and could intuitively get that I was doing something more elaborate with it. I think many artists in the 8-bit (low resolution computer) scene who I have written about on the blog, such as Cory Arcangel and Paper Rad, have a similar idea, although "elaborate" isn't necessarily the right word--Arcangel's work is quite minimal. They use old games and software because the interfaces are known. Also the programs are simple enough that as a producer you feel like you have some control over them. You aren't so dependent on others' aesthetic decisions at the engineering level.

Tom Moody, F-Factor , 2003-4. Ink on paper, linen tape, 54 x 49 in. Photo by Bill Orcutt. AY: You have these works on paper, like Swarm F-Factor, and you also make animated .gifs and other images that you present on your weblog. How do you think about the relationship between these different contexts? TM: In studio visits people often say these paper pieces look richer and more complicated in person than on the website. It's true that there are more details—there's the interaction of reflected light with paper and ink—and that there's a whole different gestalt , to use a fancy term, when you encounter the work in physical space, which the camera (and therefore the browser) doesn't capture. But I'm not complaining, since the web presence is actually leading to shows and giving me a chance to articulate my position. And articulate and articulate it… The printed works are physical objects and they're meant to be looked at in that kind of space. But I am giving more thought to web-specific or browser-specific work these days. Hence the animated .gifs and .mp3s of music I've been posting. Ultimately the work has to fit the medium.

AY: This makes me think of the continued relevance of Marshal McLuhan's statement, “the medium is the message,” particularly with so much work being made with new technology today. After working with digital tools for so long, how do you consider the issues of web-art versus gallery art or object art? TM: The medium can be the message, but it can also just be a delivery system for the content. Early net art was focused on the mechanics of the net and how information was assembled in your computer. Since then software such as music and imaging technology has vastly improved, files can be more easily compressed, and access to the net is easier for more people. You can do things on a home computer now that used to be prohibitively expensive. You can also be lo-fi and cheekily self-referential. In any case, art made with the computer has arrived—it's not just flying toasters. Instead of art about the net you have stand-alone content, which the net delivers from artist to viewer. Which can then be exchanged, appropriated, mashed up... Or not--I'm not that fanatic that everything has to be altered or collaborative. Whether to make web-based work or work for “meat space,” as the hackers call it, is more a matter of choice and what you want to say with the work. A corollary to the McLuhan quote is the minimalists' idea of "truth to materials." A work made for the web, meant to be consumed via a browser and/or speakers, is truer when displayed on the web—that is, it more accurately reflects the artist's intention—than a several-stages-removed facsimile of a work originally meant to be consumed in gallery space. The flip side is that things meant to be consumed online, sitting at your computer screen, rarely make the transition to gallery space very well. I think the web has changed the way a handful of artists are thinking about art. But as long as museums and galleries insist on “slide reviews” and don't look for the buzz online, and as long as the art market privileges painting on canvas as its main economic engine, these changes are roughly at the level of Czech writers passing around photocopies of their novels in the Soviet era. They'll have an effect about 20 years from now, if at all. A lot also depends on the future of the web, and whether it will continue as it is or be Balkanized by commerce or politics. AY: On the subject of your blog, what is the effect on your creative process of uploading every day? Are you "publishing" unfinished work? What kind of responses do you get? TM: I should say that I don't consider the blog to be "my art," or the work published there to be my only art. I'm very active on the gallery side. The weblog is a combination of things--it's a studio diary, it's an ongoing documentation of past work, and it's a place for work-in-process, as well as collaborations, original pieces made for the web, and mini-curated exhibitions of things I like (of both an art and a web-oddity nature). As I said on the blog once, I'm interested in the crossover of visual art, tech, electronic music, film, science fiction, and politics and not just replicating the art world online, with all its ancient structures and restrictions. And yes, feedback has been great and I feel like I'm part of several communities. |

| all content © 2006 Aaron Yassin |